Posted on August 6, 2019

Il-Kunsill qed jipproduċi t-traskrizzjoni tal-kontribut ta’ Pawlu Mizzi fil-fuljett tal-ewwel Fiera Internazzjonali tal-Ktieb f’Malta li saret fl-1979.

L-artiklu, The Book Industry in Malta, huwa wieħed minn tlieta biss fil-fuljett, flimkien ma’ dak miktub mill-Kap Librar tal-Libreriji, Vincent A. Depasquale u l-President ta’ Malta ta’ dak iż-żmien, Anton Buttigieg. Dan juri kemm il-kelma ta’ Mizzi kienet meqjusa importanti f’dak li għandu x’jaqsam mad-dinja tal-kotba.

L-artiklu jiddeskrivi b’mod ċar u konċiż ix-xena tal-pubblikazzjoni f’Malta. Fost l-oħrajn Mizzi jikteb dwar il-monopolju tal-pubblikaturi Brittaniċi f’Malta u kif dan il-monopolju beda jnaqqas mill-qawwa tiegħu bis-saħħa tal-emerġenza ta’ pubblikaturi Maltin. Mizzi jargumenta li b’hekk Malta setgħet tiżviluppa l-kapaċità li tkun ċentru Mediterranju tal-ktieb. L-artiklu joħodna wkoll lura fl-istorja tat-tfassil ta’ ktieb sal-faċilitajiet tal-istampar dak iż-żmien. Finalment l-artiklu jħares lejn l-ewwel tentattiv biex titwaqqaf dar tal-pubblikazzjoni, xprunat mill-imħabba lejn l-ilsien lokali, il-Malti.

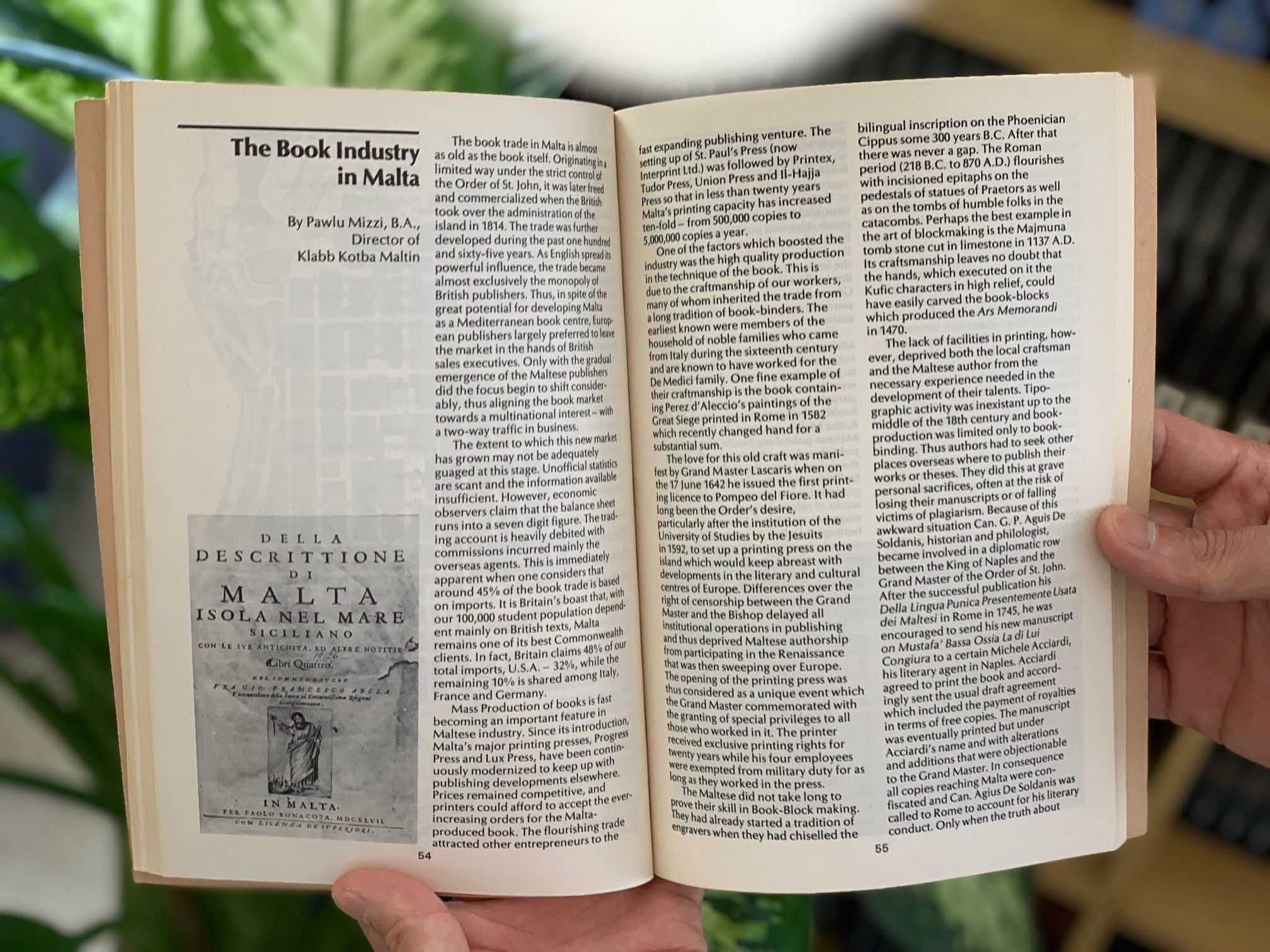

The Book Industry in Malta

By Pawlu Mizzi, B.A.,

Director of Klabb Kotba Maltin

The book trade in Malta is almost as old as the book itself. Originating in a limited way under the strict control of the Order of St.John, it was later freed and commercialized when the British took over the administration of the island in 1814. The trade was further developed during the past one hundred and sixty-five years. As English spread its powerful influence, the trade became almost exclusively the monopoly of British publishers. Thus, in spite of the great potential for developing Malta as a Mediterranean book centre, European publishers largely preferred to leave the market in the hands of British sales executives. Only with the emergence of the Maltese publishers did the focus begin to shift considerably, thus aligning the book market towards a multinational interest— with a two-way traffic in business.

The extent to which this new market has grown may not be adequately gauged at this stage. Unofficial statistics are scant and the information available insufficient. However, economic observers claim that the balance sheet runs into a seven digit figure. The trading account is heavily debited with commissions incurred mainly the overseas agents. This is immediately apparent when one considers that around 45% of the book trade is based on imports. It is Britain’s boast that, with our 100,000 student population dependent mainly on British texts, Malta remains one of its best Commonwealth clients. In fact, Britain claims 48% of our total imports, U.S.A. — 32%, while the remaining 10% is shared among Italy, France and Germany.

Mass Production of books is fast becoming an important feature in Maltese industry. Since its Malta’s major printing presses, Progress Press and Lux Press, have been continuously modernized to keep up with publishing developments elsewhere. Prices remained competitive, and printers could afford to accept the ever-increasing orders for the Malta-produced book. The flourishing trade attracted other entrepreneurs to the fast expanding publishing venture. The setting up of St. Paul’s Press (now Interprint Ltd.) was followed by Printex, Tudor Press, Union Press and II-Hajja Press so that in less than twenty years Malta’s printing capacity has increased ten-fold — from 500,000 copies to 5,000,000 copies a year.

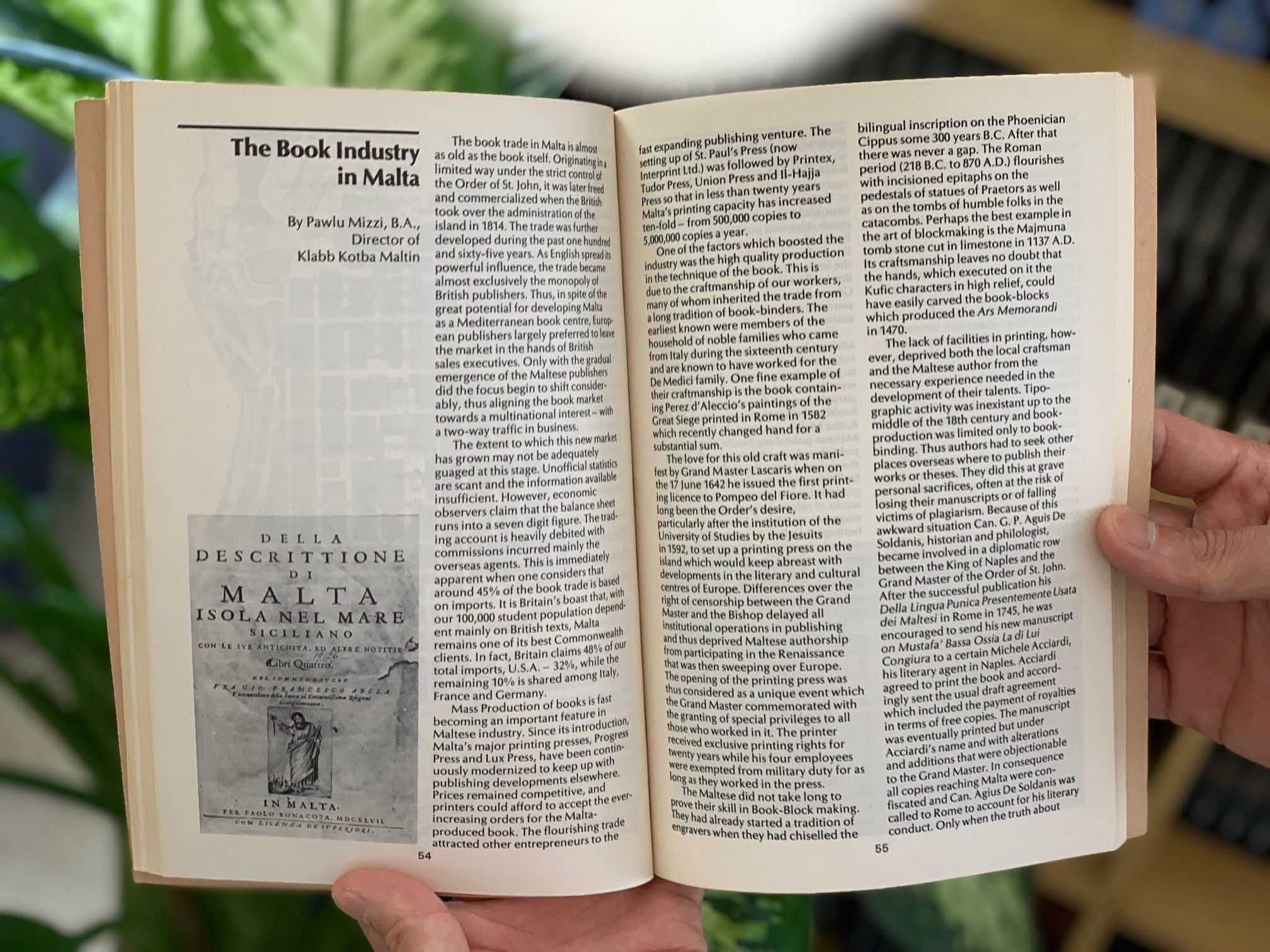

One of the factors which boosted the industry was the high quality production in the technique of the book. This is due to the craftmanship of our workers, many of whom inherited the trade from a long tradition of book-binders. The earliest known were members of the household of noble families who came from Italy during the sixteenth century and are known to have worked for the De Medici family. One fine example of their craftmanship is the book contain ing Perez d’Aleccio’s paintings of the Great Siege printed in Rome in 1582 which recently changed hand for a substantial sum.

The love for this old craft was manifest by Grand Master Lascaris when on the 17 June 1642 he issued the first printing licence to Pompeo del Fiore. It had long been the Order’s desire, particularly after the institution of the University of Studies by the Jesuits in 1592, to set up a printing press on the island which would keep abreast with developments in the literary and cultural centres of Europe. Differences over the right of censorship between the Grand Master and the Bishop delayed all institutional operations in publishing and thus deprived Maltese authorship from participating in the Renaissance that was then sweeping over Europe. The opening of the printing press was thus considered as a unique event which the Grand Master commemorated with the granting of special privileges to all those who worked in it. The printer received exclusive printing rights for twenty years while his four employees were exempted from military duty for as long as they worked in the press.

The Maltese did not take long to prove their skill in Book-Block making. They had already started a tradition of engravers when they had chiselled the bilingual inscription on the Phoenician Cippus some 300 years B.C. After that there was never a gap. The Roman period (218 B.C. to 870 AD.) flourishes with incisioned epitaphs on the pedestals of statues of Praetors as well as on the tombs of humble folks in the catacombs. Perhaps the best example in the art of blockmaking is the Majmuna tomb stone cut in limestone in 1137 A.D. Its craftsmanship leaves no doubt that the hands, which executed on it the Kufic characters in high relief, could have easily carved the book-blocks which produced the Ars Memorandi in 1470.

The lack of facilities in printing, however, deprived both the local craftsman and the Maltese author from the necessary experience needed in the development of their talents. Tipographic activity was inexistant up to the middle of the 18th century and book-production was limited only to book-binding. Thus authors had to seek other places overseas where to publish their works or theses. They did this at grave personal sacrifices, often at the risk of losing their manuscripts or of falling victims of plagiarism. Because of this awkward situation Can. G. P. Aguis De Soldanis, historian and philologist, became involved in a diplomatic between the King of Naples and the Grand Master of the Order of St. John. After the successful publication his Della Lingua Punica Presentemente Usata dei Maltesi in Rome in 1745, he was encouraged to send his new manuscript on Mustafa’ Bassa Ossia La di Lui Congiura to a certain Michele Acciardi, his literary agent in Naples. Acciardi agreed to print the book and accordingly sent the usual draft agreement which included the payment of royalties in terms of free copies. The manuscript was eventually printed but under Acciardi’s name and with alterations and additions that were objectionable to the Grand Master. In consequence all copies reaching Malta were confiscated and Can. Agius De Soldanis was called to Rome to account for his literary conduct. Only when the truth about Acciardi’s printing piracy became known was Can. Agius De Soldanis exculpated of the charge of sedition. In compensation for the hardship he was forced to suffer and in recognition of his literary talents he was created the first librarian of the newly formed Biblioteca Tanseana now the National Library of Malta.

The consciousness in the important role of the book coincided with the pioneering interest in the study of the Maltese language. De Soldanis was himself keen in diffusing it among the Knights of the Order of St. John in order to create a closer link between the rulers and the ruled. These views were also shared by Mikiel Anton Vassalli, another Maltese scholar, later also known as father of the Maltese language, who believed that the propagation of books in the vernacular was the most efficient media in the conquest of ignorance among the Maltese masses. Unfortunately his patriotic zeal in the Discorso Preliminare received little attention from the ruling authorities and his frequent appeals were discarded as revolutionary and Jacobite. Thus the entire nineteenth century was lost to many publications in Maltese and the few that were printed lacked the attraction needed to found the basis for a stable industry.

The first real attempt to start a Maltese publishing house came in 1895. Alphonse Maria Galea, a philantropist and social worker, who started an apprentice course in printing at the Salesian Fathers in Sliema, organized a series of publications called Cotba tal-Mogħdija taż-Żmien. The books were attractively produced and varied in interest. In spite of their relatively high price, two pence per copy — which was then almost the entire pay packet for the day — it attracted enough customers to make the venture economically viable. More than three thousand copies in each title were sold and for more than 20 years the Maltese reading public was secured of a much needed educational commodity. When the Maltese alphabet was standardized in 1921, the urge for more Maltese literature grew and later with the emergence of Maltese literary movements, organized publishing was again taken in hand by Dr. Guze in 1938. In two years Bonnici succeeded in publishing six titles but his untimely death relegated publishing to just a bookselling activity and for many years the Maltese book depended solely on the initiative of the authors themselves. Booksellers like A. J. Aquilina & Co., Giovanni Muscat, Cumbo and others were the only sources for the Maltese authors.

The growing awareness of the Maltese language as an integral part of national identity inspired literary circles to produce more works. As more books were produced more consumers were attracted and in the economically healthy climate that was created, Klabb Kotba Maltin was born. At first this Maltese publishing house planned to publish only one book a month, but as the demand grew the Klabb’s publishing facilities were extended. It launched a graded children’s section, published works of reference and issued a monthly magazine on Malta’s history and heritage. Merlin Library, too, joined the industry with production of more books particularly with Maltese translations of Ladybird books. In this way the efforts to our publishers proved fruitful and the Maltese book market became richer by at least 150 new titles a year.

These facts and figures in Maltese publishing are good pointers to an efficient book industry. The ingredients are all there: modern machinery, experience, technical know-how and above all entrepreneurship and enthusiasm. What is perhaps needed are first-class producers with visions that are wider and better than these ordinary shopkeepers. This is what the Prime Minister hinted at when, in a message to the nation broadcast on television on the 12 July 1976, he suggested that Malta’s book industry could become the pride of the Mediterranean.

*

Share Article

{startDate:"2021-03-24 10:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-24 11:00:00",summary:"Preżentazzjoni ta’ ktieb: 'Mattia Preti: Life and Works' ta’ Keith Sciberras - Midsea Books",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2021-03-24 12:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-24 13:00:00",summary:"Tnedija tal-ktieb 'Kaligula' ta' Albert Camus maqlub għall-Malti - Faraxa Publishing",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-24 13:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-24 14:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ ktieb: 'Leading Cases in Maltese Administrative Law' - Kite Group",timest:"1:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-24 14:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-24 15:00:00",summary:"Il-Malti: Protagonist f’Ħażna Diġitali Ġdida - GħMU",timest:"2:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-24 16:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-24 17:00:00",summary:"'Kwarantina' ta’ Jim Crace maqlub għall-Malti: Tnedija - Horizons",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-25 10:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-25 11:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta' ktieb: 'Ċelel Bla Ħitan' - Horizons",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2021-03-25 12:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-25 14:00:00",summary:"Il-klabb tal-kotba: Niddiskutu 'Firebird' ma’ Mark Doty - KNK",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-25 13:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-25 14:00:00",summary:"Ir-rabta tal-filosofija mat-teknoloġija u l-intelliġenza artifiċjali - Id-Dipartiment tal-Filosofija",timest:"1:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-25 14:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-25 15:00:00",summary:"Ġenerożità, Imħabba, Kreattività, Kuntentizza u Rispett: 'Ġikkur' - Faraxa Publishing",timest:"2:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-25 16:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-25 17:00:00",summary:"L-Ombudsman - Flessibbli Wisq mal-Amministrazzjoni Pubblika? - BDL Books",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-25 18:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-25 19:00:00",summary:"Tnedija tal-ktieb ta’ Alfred Sant 'Confessions of a European Maltese - The Middle Years' - SKS",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-26 10:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-26 11:00:00",summary:"Preżentazzjoni ta’ ktieb: 'Ir-Redentur: History, Art, Cult' ta’ Jonathan Farrugia (ed.) - Midsea Books",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2021-03-26 12:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-26 13:00:00",summary:"'Leħen il-Malti': 90 sena, 40 edizzjoni - GħMU",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-26 14:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-26 15:00:00",summary:"Taboo! Il-kittieb Malti għadu jrid joqgħod attent x’jista’ u ma jistax jikteb, fl-2021? - Merlin Publishers",timest:"2:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-26 15:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-26 16:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ ktieb: 'Tourism and the Maltese Islands – Observations, reflections and proposals' - Kite Group",timest:"3:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-26 16:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-26 17:00:00",summary:"L-intervista lill-awtur ma' Mark Doty - KNK",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-03-26 19:00:00",endDate:"2021-03-26 21:00:00",summary:"Palk Ħieles waqt il-Festival tal-Ktieb fuq il-Kampus - Inizjamed, KNK",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-02 19:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-02 19:00:00",summary:"IS-SERATA TAL-FTUĦ U Ċ-ĊERIMONJA TAL-GĦOTI TAL-PREMJIJIET TAL-PREMJU TERRAMAXKA 2021 - KNK",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-03 10:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-03 11:00:00",summary:"SESSJONI TA’ QARI MA’ RUTH FRENDO: 'L-ĠĦOĠOL TAD-DEHEB' U 'ID-DINJA TAL-ORSINI' - MILLER",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-03 10:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-03 12:00:00",summary:"TNEDIJA TA’ KOTBA: PUBLIKAZZJONIJIET TEATRU MALTA - TEATRU MALTA",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-03 17:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-03 18:30:00",summary:"PREŻENTAZZJONI TA’ KTIEB: 'IL BOSCAIOLO' (ALGRA EDITORE) - IIC",timest:"5:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-03 18:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-03 19:00:00",summary:"TNEDIJA TA’ KTIEB: 'STORJA TAL-ILSIEN U L-LETTERATURA MALTIJA – KRONOLOĠIJA' - AKKADEMJA TAL-MALTI / HERITAGE MALTA",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-03 18:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-03 19:00:00",summary:"'IL-KOTBA JIEĦDU L-ĦAJJA' - DANUSAN",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-03 19:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-03 20:00:00",summary:"IKKANĊELLAT - TNEDIJA TA’ KTIEB: 'THE MALTESE LEGAL SYSTEM' - MALTA UNIVERSITY PRESS",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-03 19:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-03 21:00:00",summary:"IRVINE WELSH: DWAR LETTERATURA U DJ SETS - KNK",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 09:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 10:30:00",summary:"KWIZZ: FEJN HEMM IL-KOTBA HEMM IL-MAĠIJA - KNK",timest:"9:30 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 10:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 11:00:00",summary:"SESSJONI TA’ QARI MA’ RUTH FRENDO: 'L-ĠĦOĠOL TAD-DEHEB' U 'ID-DINJA TAL-ORSINI' - MILLER",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 17:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 18:30:00",summary:"DRAMM: 'PITO U PITA' - HORIZONS",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 17:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 17:45:00",summary:"PREŻENTAZZJONI TA’ KTIEB: 'KÒSHARI. RACCONTI ARABI E MALTESI' - IIC",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 18:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 19:00:00",summary:"CHUIZ JEW KWIZZ? - GĦAQDA TAL-MALTI – UNIVERSITÀ",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 18:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 19:00:00",summary:"L-ISFIDA MSELLA - SAN ANTON SCHOOL / KNK",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 18:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 19:00:00",summary:"'IL-KOTBA JIEĦDU L-ĦAJJA' - DANUSAN",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 19:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 20:00:00",summary:"TNEDIJA TA’ KTIEB: 'WORKING LIFE AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF MALTA' - MALTA UNIVERSITY PRESS",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 19:15:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 20:00:00",summary:"TAĦDITA INFORMATTIVA: X’HEMM GĦALIJA - CREATIVE EUROPE DESK MALTA",timest:"7:15 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 19:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 21:00:00",summary:"SKAMBJI LETTERARJI: KONVERŻAZZJONI BEJN IRVINE WELSH U IMMANUEL MIFSUD MA’ MARK VELLA (MOD.) - KNK",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-04 20:15:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 21:15:00",summary:"TNEDIJA TA’ KTIEB: 'VARJAZZJONIJIET TAS-SKIET' TA’ NADIA MIFSUD - EDE BOOKS",timest:"8:15 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 09:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 10:30:00",summary:"KWIZZ: FEJN HEMM IL-KOTBA HEMM IL-MAĠIJA - KNK",timest:"9:30 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 10:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 11:00:00",summary:"SESSJONI TA’ QARI MA’ RUTH FRENDO: 'L-ĠĦOĠOL TAD-DEHEB' U 'ID-DINJA TAL-ORSINI' - MILLER",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 17:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 17:45:00",summary:"PREŻENTAZZJONI TA’ KTIEB: 'WHERE WILD ORCHIDS GROW' TA’ JOHAN SIGGESSON - MARVELLOUS MALTA",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 17:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 18:00:00",summary:"TNEDIJA TA’ KTIEB: IL-FORMA TAL-ILMA (LA FORMA DELL’ACQUA, ANDREA CAMILLERI) - IIC / MERLIN PUBLISHERS",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 17:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 18:30:00",summary:"TNEDIJA TA’ KTIEB: 'EXODUS OF THE STORKS' (L-EŻODU TAĊ-ĊIKONJI, WALID NABHAN) - PETER OWEN PUBLISHERS / KNK",timest:"5:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 18:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 19:00:00",summary:"SESSJONI TA’ QARI U FFIRMAR TA’ KTIEB: 'THE PATH TO REDEMPTION' TA’ STEPHEN MANGION - MILLER DISTRIBUTORS",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 18:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 19:00:00",summary:"INGĦAQDU MAGĦNA GĦAL SIEGĦA MAKKJETT’GĦANA - GĦAQDA TAL-MALTI – UNIVERSITÀ",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 18:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 19:00:00",summary:"'IL-KOTBA JIEĦDU L-ĦAJJA' - DANUSAN",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 19:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 20:00:00",summary:"IL-KONKORS NAZZJONALI TAL-POEŻIJA DOREEN MICALLEF 2021: L-GĦOTI TAL-PREMJIJIET - KNK",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 19:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 20:00:00",summary:"IKKANĊELLAT - PREŻENTAZZJONI TA’ KTIEB: 'REQUIEM PER UN FASCISTA MALTESE' (REQUIEM FOR A MALTA FASCIST, FRANCIS EBEJER) - IIC",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 19:15:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 20:00:00",summary:"TNEDIJA TA’ 9 KOTBA ĠODDA - HORIZONS",timest:"7:15 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 20:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 21:00:00",summary:"TNEDIJA TA’ KTIEB: 'STRANGERS I’LL NEVER FORGET' TA’ MJ CAMILLERI - EDE BOOKS",timest:"8:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 20:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 20:45:00",summary:"STAND-UP MINN RON BRIFFA - KITE GROUP",timest:"8:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 20:15:00",endDate:"2021-11-05 21:15:00",summary:"TAĦDITA BEJN IR-RETTURI - ID-DOKUMENTAZZJONI TAL-LEGAT TAL-UNIVERSITÀ TA’ MALTA - MUP",timest:"8:15 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-05 20:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-04 21:30:00",summary:"IL-BIEB DEJJEM IMBEXXAQ: OMAĠĠ LIL OLIVER FRIGGIERI - KNK",timest:"8:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 10:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 12:00:00",summary:"STEJJER, LOGĦOB U KRAFTS GĦAT-TFAL - FARAXA PUBLISHING",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 10:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 11:30:00",summary:"PREŻENTAZZONI TA’ KTIEB: 'SWEET MALTESE MOMENTS' TA’ PAUL FENECH - MIDSEA BOOKS",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 10:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 12:30:00",summary:"IL-PRESIDENT GEORGE VELLA JIFFIRMA L-KOTBA 'TISJIR MILL-QALB' - MILLER",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 10:30:00",endDate:"1970-01-01 00:00:00",summary:"QARI MINN AUNTY SAB GĦAL TFAL BEJN 3-6 SNIN - MERLIN PUBLISHERS",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 11:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 00:30:00",summary:"SESSJONI TA’ QARI MA’ RUTH FRENDO: 'L-ĠĦOĠOL TAD-DEHEB' U 'ID-DINJA TAL-ORSINI' - MILLER - SOUTH HALL",timest:"11:30 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 12:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 13:00:00",summary:"IR-REBBIEĦA TAL-EUPL TUL IS-SNIN - CREATIVE EUROPE DESK MALTA",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 13:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 15:00:00",summary:"DRAMM: 'PITO U PITA' - HORIZONS",timest:"1:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 13:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 14:00:00",summary:"QARI MIR-REBBIEĦA TAL-EUPL: 'KISSIRTU KULLIMKIEN' - CREATIVE EUROPE DESK MALTA",timest:"1:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 14:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 15:30:00",summary:"IKKANĊELLAT - TREASURE TROVES OF MALTESE HISTORY – MUP",timest:"2:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 15:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 15:45:00",summary:"ĊERIMONJA TA’ PREMJAZZJONI: IL-KOMPETIZZJONI TAL-KITBA BIL‐ĠERMANIŻ ‘CITY DREAMS’ (STADT‐TRÄUME) - GERMAN-MALTESE CIRCLE / DEPARTMENT OF GERMAN, UOM",timest:"3:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 16:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 17:00:00",summary:"PREŻENTAZZJONI TA’ KTIEB: 'WITH ALL DUE RESPECT' TA’ JEFFREY PULLICINO ORLANDO - MILLER",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 16:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 16:45:00",summary:"PREŻENTAZZJONI TA’ KTIEB: 'WHERE WILD ORCHIDS GROW' TA’ JOHAN SIGGESSON - MARVELLOUS MALTA",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 16:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 17:30:00",summary:"'IL-KOTBA JIEĦDU L-ĦAJJA' - DANUSAN",timest:"4:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 17:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 18:00:00",summary:"TNEDIJA TA’ KOTBA: KITBA MALTIJA ĠDIDA BL-INGLIŻ - PRASPAR PRESS u KNK",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 17:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 17:45:00",summary:"'IL-FATAT KAĦLANI': QARI MA’ CLARE AZZOPARDI U LEANNE ELLUL - MERLIN PUBLISHERS",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 17:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 18:30:00",summary:"SESSJONI TA’ FFIRMAR TAL-KOTBA MA’ IRA LOSCO - KIWI PUBLICATIONS",timest:"5:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 18:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 19:00:00",summary:"'ĦASSARTEK': KTIEB TAL-POEŻIJA TAT-TĦASSIR - MATTHEW SCHEMBRI",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 18:15:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 19:15:00",summary:"SEMINAR DWAR IL-PRODUZZJONI TAL-KOTBA - GUTENBERG PRESS",timest:"6:15 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 19:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 20:00:00",summary:"PREŻENTAZZJONI TAT-TRILOĠIJA: 'IL VURRICATORE', 'AI CONFINI DELL’INFERNO', 'GLI STRATEGHI DEL MALE' TA’ I.M.D - IIC",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 19:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 20:30:00",summary:"ĊAR KRISTALL? IT-TRADUZZJONI TAL-POEŻIJA - INIZJAMED",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 19:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 20:30:00",summary:"IL-LETTERATURA MALTIJA MADWAR ID-DINJA - KNK",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 20:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 21:00:00",summary:"IKKANĊELLAT - 'ORGOGLIO SICILIANO' (BONFIRRARO EDITORE) - IIC",timest:"8:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-06 20:45:00",endDate:"2021-11-06 21:45:00",summary:"SKRINJAR TA’ FILM: TREVOR ŻAHRA - IR-REBBIEĦ TAL-PREMJU NAZZJONALI TAL-KTIEB GĦALL-KONTRIBUT SIEWI FIL-QASAM TAL-KOTBA - KNK",timest:"8:45 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 09:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 11:00:00",summary:"SESSJONI TA’ QARI MA’ RUTH FRENDO: ‘L-ĠĦOĠOL TAD-DEHEB’ U ‘ID-DINJA TAL-ORSINI’ – MILLER",timest:"9:30 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 10:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 12:00:00",summary:"IL-PRESIDENT GEORGE VELLA JIFFIRMA L-KOTBA 'TISJIR MILL-QALB' - MILLER",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 10:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 11:15:00",summary:"LUPU LUPETTU U ĦBIEB ĠODDA U ANTIKI - MERLIN PUBLISHERS",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 11:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 13:30:00",summary:"DRAMM: 'PITO U PITA' - HORIZONS",timest:"11:30 AM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 12:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 13:30:00",summary:"TAĦDITA INFORMATTIVA: X’HEMM GĦALIJA - CREATIVE EUROPE DESK MALTA",timest:"12:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 13:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 14:30:00",summary:"IKKANĊELLAT - IFFIRMAR TA’ KTIEB: 'SLIEMA WIVES: THE NEW BREED'

- MIDSEA BOOKS",timest:"1:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 14:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 15:00:00",summary:"‘DO PUPPETS TALK?’ - XOW BIL-MARJUNETTI - MERLIN LIBRARY",timest:"2:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 15:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 16:30:00",summary:"STEJJER, LOGĦOB, U KRAFTS GĦAT-TFAL - FARAXA PUBLISHING",timest:"3:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 16:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 16:45:00",summary:"‘IR-RUMANZINI’ - MERLIN PUBLISHERS",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 16:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 17:30:00",summary:"'IL-KOTBA JIEĦDU L-ĦAJJA' - DANUSAN",timest:"4:30 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 17:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 18:00:00",summary:"TNEDIJA TA’ KTIEB: L-40 EDIZZJONI TA’ 'LEĦEN IL-MALTI' - GĦAQDA TAL-MALTI - UNIVERSITÀ",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 17:00:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 17:45:00",summary:"PREŻENTAZZJONI TA’ KTIEB: 'WHERE WILD ORCHIDS GROW' TA’ JOHAN SIGGESSON - MARVELLOUS MALTA",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2021-11-07 17:30:00",endDate:"2021-11-07 20:00:00",summary:"SKRINJAR TA’ FILM: 'IS-SRIEP REĠGĦU SARU VELENUŻI' - KNK",timest:"5:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 09:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 13:00:00",summary:"Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall",timest:"9:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 10:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 10:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: Osbert and friends – Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (EN)",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 10:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 10:40:00",summary:"Produzzjoni ŻiguŻajg għal tfal ta’ 8 snin jew iżgħar – Theatre (EN)",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 11:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: Il-Kavallier Għatxan - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) – Readers’ Hub (MT)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 12:00:00",summary:"Inkewsu Storja - Malta Libraries - Authors’ Hub (MT/EN)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 12:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 00:40:00",summary:"Produzzjoni ŻiguŻajg għal tfal bejn 8 u 12-il sena - Theatre (MT)",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 19:00:00",summary:"Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 18:00:00",summary:"Three Little Pigs (tfal minn 3 sa 6 snin) - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 21:00:00",summary:"Podcast Live - Jon Mallia - Readers’ Hub",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 17:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 18:15:00",summary:"Preżentazzjoni ta’ ktieb: 'Il-Forka ta’ Malta u l-Piena Kapitali barra minn xtutna' - Ronald Bugeja - Authors’ Hub (MT)",timest:"5:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 19:00:00",summary:"The Very Hungry Caterpillar (3-6 year olds) - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 19:00:00",summary:"L-Isfida Msella - San Anton u KNK - Blue Hall (MT)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 19:00:00",summary:"Meetup - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Stand WCM (MT/EN)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 18:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 19:15:00",summary:"It-tnedija tal-Konkors ta’ Letteratura għaż-Żgħażagħ - KNK u Aġenzija Żgħażagħ - Authors’ Hub (MT)",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 19:30:00",summary:"L-Ilma - Ibda Minnek - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (MT)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 20:00:00",summary:"Wikipedia Editing Workshop - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Rainbow Hall (MT/EN)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 19:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 20:30:00",summary:"Qari ta’ Poeżija minn Poeti Kontemporanji - Kotba Calleja – Authors’ Hub (MT)",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 19:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 21:00:00",summary:"Demgħat tas-Silġ? Omaġġ lil Mario Azzopardi - KNK - Theatre (MT",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-23 20:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-23 20:30:00",summary:"Water - Be the Change - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (EN)",timest:"8:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 09:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 13:00:00",summary:"Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall",timest:"9:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 10:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 10:40:00",summary:"Produzzjoni ŻiguŻajg għal tfal ta’ 8 snin jew iżgħar – Theatre (EN)",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 23:30:00",summary:"L-Ilma - Ibda Minnek - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (MT)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 12:00:00",summary:"MAPEP: Kif u x’fatta? - Malta Libraries - Authors’ Hub (MT/EN)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 12:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 12:40:00",summary:"Produzzjoni ŻiguŻajg għal tfal bejn 8 u 12-il sena - Theatre (MT)",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 17:45:00",summary:"Meetup - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Stand WCM (MT/EN)",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 17:30:00",summary:"Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 19:00:00",summary:"Tnedija tal-Annwal tal-Illustrazzjonijiet Maltin - Malta Community of Illustrators - Illustrators’ Hub (EN)",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 18:00:00",summary:"Three Little Pigs (3 sa 6 snin) - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 17:45:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 18:45:00",summary:"Stejjer tal-ivvjaġġar bejn Malta u l-Ewropa fis-seklu 17 u 18 - L-Ambaxxata Franċiża f’Malta - Authors’ Hub (EN)",timest:"5:45 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 18:45:00",summary:"Wiki Loves - Information Session - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Blue Hall (MT/EN)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-10-24 20:00:00",summary:"Il-Promoturi tal-Qari - Aġenzija Nazzjonali tal-Litteriżmu - Theatre (MT)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 18:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 19:15:00",summary:"Qari ta’ poeżija: 'The Bell' minn Maria Grech Ganado, xogħol ġdid għadu fil-proċess - Kotba Calleja - Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 19:30:00",summary:"L-Ilma - Ibda Minnek - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (EN)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 20:00:00",summary:"Kwiżż: Mill-basla tax-xagħar sa qasbet is-sieq - Għaqda tal-Malti - Università - Authors’ Hub (MT)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 20:00:00",summary:"Joe Sacco f’konverżazzjoni ma’ James Debono - KNK - Blue Hall (EN)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 19:15:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 20:30:00",summary:"Iltaqa' mal-Artist Sessjoni ma' Trevor Żahra - Il-Kunsill Malti għall-Arti - Illustrators’ Hub (MT)",timest:"7:15 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 19:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 20:30:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ ktieb: 'The front page on the front line' - Klabb Kotba Maltin - Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-24 20:15:00",endDate:"2022-11-24 21:00:00",summary:"Taħdita: 'L-Ibleh' - SKS - Blue Hall (MT)",timest:"8:15 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 09:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 13:00:00",summary:"Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall",timest:"9:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 10:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 10:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: L-Eroj tal-Ilma – Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (MT)",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 10:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 10:40:00",summary:"Produzzjoni ŻiguŻajg – Piġama Rrigata: Iltaqa’ ma’ John Boyne - Theatre (EN)",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 11:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: A Journey with the Energetic Four – The Renewables – Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (EN)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 12:00:00",summary:"Kellek xi dubju? – MHUX ISSAQSI LIL-LIBRAR! - Malta Libraries - Authors’ Hub (MT/EN)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 11:45:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 12:45:00",summary:"Sessjoni mill-awtur mat-tfal u l-ġenituri - Merlin Library - Stand Merlin Library (MT)",timest:"11:45 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 12:00:00",endDate:"2022-10-13 00:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: L-Erba’ Żgħażagħ u l-Kumpanija tal-Ilma – Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (MT)",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 12:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 12:40:00",summary:"Produzzjoni ŻiguŻajg - Iltaqa’ mal-awtur ta’ The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas - Theatre (EN)",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 17:45:00",summary:"Sqallija, bliet u miti - Istituto Italiano di Cultura - Authors’ Hub (IT)",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 18:00:00",summary:"Rakkuntar ta’ stejjer permezz ta’ Moviment u Żfin (3-6 snin) - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 18:00:00",summary:"Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 17:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 18:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni Iltaqa' mal-Artist mal-Komunità Maltija tal-Illustraturi - Il-Kunsill Malti għall-Arti - Illustrators’ Hub (EN)",timest:"5:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 17:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 19:00:00",summary:"Il-Konkors Nazzjonali tal-Poeżija Doreen Micallef 2022: l-Għoti tal-Premjijiet - KNK - Blue Hall (MT)",timest:"5:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 18:45:00",summary:"Preżentazzjoni ta’ ktieb: 'Non è al momento raggiungibile' (Mondadori) ta’ Valentina Farinaccio - Istituto Italiano di Cultura - Authors’ Hub (IT)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 19:00:00",summary:"Rakkuntar ta’ stejjer permezz ta’ Moviment u Żfin (6-12-il sena) - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 19:00:00",summary:"Meetup - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Stand WCM (MT/EN)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 18:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 19:00:00",summary:"L-Ilma - Ibda Minnek - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (MT)",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 19:45:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ ktieb: 'Sajf', Rumanz ta’ Ryan Falzon - Kotba Calleja - Illustrators’ Hub (MT)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 20:00:00",summary:"Qari: Marie Gamillscheg mir-rumanz tagħha 'Aufruhr der Meerestiere' (2022) - German-Maltese Circle / UM Department of German - Rainbow Hall (DE)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 20:00:00",summary:"Edit-a-thon - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Stand WCM (MT/EN)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 19:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 20:30:00",summary:"Taħdita fuq ktieb: 'In the Footsteps of Antonello da Messina' ta’ Charlene Vella - Midsea Books - Blue Hall (EN)",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 19:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 20:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ ktieb: L-Antoloġija tal-Letteratura Mqarba - Dar Camilleri - Authors’ Hub (MT)",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 19:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 21:00:00",summary:"John Boyne f’konverżazzjoni ma’ Leanne Ellul - NBC - Theatre (EN)",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-25 20:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-25 20:30:00",summary:"L-Ilma - Ibda Minnek - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (EN)",timest:"8:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 09:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 11:00:00",summary:"Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall",timest:"9:30 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 09:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 10:15:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari ma’ Lucienne Cassar - Pandora Books - Authors’ Hub (MT)",timest:"9:30 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 10:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 11:00:00",summary:"Taħdita: 'Society Fashion in Malta' ta’ Caroline Tonna - Midsea Books - Blue Hall (MT)",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 10:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 11:00:00",summary:"Pinġi ma’ Gattaldo: workshop esklussiv għal tfal bejn 7 u 12-il sena - KNK - Illustrators’ Hub (EN)",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 10:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 11:00:00",summary:"Book Launch: 'Tita Tmiss l-Art' by Glen Calleja and Clare Azzopardi - Kotba Calleja - Kotba Calleja Stand (MT)",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 12:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ ktieb: 'Asher and the Extraordinary Journey' ta' Carl-Thomas Tonna - Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 12:00:00",summary:"Simon Trewin - Qrara ta’ aġent letterarju - KNK - Authors’ Hub (EN)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 00:00:00",summary:"Meetup - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Stand WCM (MT/EN)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 11:15:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 11:45:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ ktieb: 'Tita Tmiss l-Art' ta’ Glen Calleja u Clare Azzopardi - Kotba Calleja - Blue Hall (MT)",timest:"11:15 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 11:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 00:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta' informazzjoni dwar il-fondi u l-istrateġija tal-Kunsill Malti għall-Arti - Il-Kunsill Malti għall-Arti - Illustrators’ Hub (EN)",timest:"11:30 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 11:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-04 12:12:00",summary:"Iffirmar ta' ktieb: 'Il-Ġurnalista, l-Istorja ta’ Daphne Caruana Galizia’ - Midsea Books",timest:"11:30 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 12:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 13:00:00",summary:"The Very Hungry Caterpillar (6 sa 12-il sena) - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 12:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 15:00:00",summary:"Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 12:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 14:30:00",summary:"Speed Date Letterarja - KNK - Readers’ Hub (EN)",timest:"12:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 13:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 15:00:00",summary:"Pirates of Maltaland! (6 sa 12-il sena) - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"1:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 14:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 15:00:00",summary:"Taħdita: Awtoppubblikar - Enfasi fuq il-kwalità - Authors’ Hub (MT)",timest:"2:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 15:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 16:00:00",summary:"Ċerimonja ta’ Għoti ta’ Premju: Konkors ta’ Kitba bil-Ġermaniż ‘TierWelten’ - German Maltese Circle / Department of German, UOM - Blue Hall (DE)",timest:"3:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 15:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 16:00:00",summary:"Spettaklu bil-marjunetti u qari ta’ stejjer - Merlin Library - Rainbow Hall (MT)",timest:"3:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 16:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 17:00:00",summary:"Wikipedia Editing Workshop - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Blue Hall (MT/EN)",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 16:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 17:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni: 'Iltaqa' mal-Pubblikatur' ma' Chris Gruppetta u Joseph Mizzi - Il-Kunsill Malti għall-Arti - Illustrators’ Hub (MT)",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 16:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 17:00:00",summary:"Produzzjoni ŻiguŻajg: Coco the Singer and the Chocolate Finger (8 snin u akbar) - Theatre (EN)",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 18:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ kotba: 'Scintillas: New Maltese Writing 2' u 'The Lives and Deaths of K. Penza' – Praspar Press - Authors’ Hub (EN)",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 18:00:00",summary:"The Clown Tells a Story! (6 sa 12-il sena) - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 17:15:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 18:00:00",summary:"Albert Camus and Annie Ernaux, two French Nobel Prizes in Literature – French Embassy in Malta – Blue Hall (EN)",timest:"5:15 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 19:00:00",summary:"Meetup - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Stand WCM (MT/EN)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 19:00:00",summary:"The Clown Tells a Story! (6 sa 12-il sena) - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 18:15:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 19:30:00",summary:"Diskussjoni: X’tiswa stampa – forom ta’ rakkuntar ta’ stejjer viżwali - KNK - Blue Hall (EN)",timest:"6:15 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 18:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 19:15:00",summary:"Il-Produzzjoni tal-Kotba - Gutenberg Press - Illustrators’ Hub (EN)",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 18:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 19:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari ma’ Nicola Kearns - Authors’ Hub (EN)",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 19:30:00",summary:"L-Ilma - Ibda Minnek - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (MT)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 20:00:00",summary:"Edit-a-thon - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Stand WCM (MT/EN)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 19:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 20:30:00",summary:"Diskussjoni: Xejn ġdid taħt il-kappa tax-xemx? Il-ġurnaliżmu f’Malta 20 sena wara r-rumanz - Merlin Publishers - Rainbow Hall (MT)",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 19:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 20:30:00",summary:"Poeżija Slam - Għaqda tal-Malti - Università - Illustrators’ Hub (MT)",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 19:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 21:00:00",summary:"Wiri ta’ film: Rena Balzan, Rebbieħa tal- Premju Nazzjonali tal-Ktieb 2021 għall-Kontribut Siewi fil-Qasam tal-Kotba u l-Letteratura - KNK - Theatre (MT)",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 20:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 20:30:00",summary:"L-Ilma - Ibda Minnek - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (EN)",timest:"8:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-26 20:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-26 21:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ ktieb: 'Ir-Re Borg' ta’ Aleks Farrugia- SKS - Authors’ Hub (MT)",timest:"8:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 09:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 11:00:00",summary:"Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall",timest:"9:30 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 09:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 11:00:00",summary:"The Clown Tells a Story! - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"9:30 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 10:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 12:00:00",summary:"Il-President George Vella jiffirma l-kotba Tisjir mill-Qalb - Agenda Bookshop - Stand Agenda Bookshop",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 11:30:00",summary:"L-Ilma - Ibda Minnek - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (MT)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 11:45:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ ktieb: 'Tita Tmiss l-Art' ta’ Glen Calleja u Clare Azzopardi - Kotba Calleja - Authors’ Hub (MT)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 00:00:00",summary:"Spettaklu bil-marjunetti u qari ta’ stejjer - Merlin Library - Rainbow Hall (MT)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 00:00:00",summary:"Meetup - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Stand WCM (MT/EN)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 11:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 12:00:00",summary:"Produzzjoni ŻiguŻajg: Coco the Singer and the Chocolate Finger (8 sa 12-il sena) - Theatre (EN)",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 14:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 15:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ kotba: 'Mikelin' u 'Noè e lo scoiattolo giocherellone' - KNK u Istituto Italiano di Cultura - Authors’ Hub (IT)",timest:"2:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 14:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 15:00:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: Osbert and Friends – Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (EN)",timest:"2:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 15:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 16:00:00",summary:"Iffirmar ta’ kotba ma' Lorraine Galea - Pandora Books - Stand Pandora Books (MT/EN)",timest:"3:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 15:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 16:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ Leħen il-Malti għadd 41 - Għaqda tal-Malti - Università - Blue Hall (MT)",timest:"3:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 15:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 16:00:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: L-istejjer ta’ Zoe u d-Dragun waqt Żmien il-Pandemija tal-Covid - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (MT)",timest:"3:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 16:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 16:45:00",summary:"Preżentazzjoni ta’ ktieb: 'A tavola con gli antichi romani' (Efesto Edizioni) ta’ Giorgio Franchetti - Istituto Italiano di Cultura - Authors’ Hub (IT)",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 16:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 17:00:00",summary:"Wikipedia Editing Workshop - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Rainbow Hall (MT/EN)",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 16:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 17:30:00",summary:"Diskussjoni: L-illustrazzjoni u l-kotba bl-istampi għodda għall-edukazzjoni - Il-Kunsill Malti għall-Arti - Illustrators’ Hub (EN)",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 18:00:00",summary:"Il-Ħajja f’Distopja - Ir-rumanz TÜK mill-awtur Ukren Art Antonian - Blue Hall (UA)",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 20:00:00",summary:"Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 17:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 18:30:00",summary:"Live Animal Session! - Fondazzjoni Inspire - Sensory Friendly Room @ Rainbow Hall (EN)",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 17:30:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 18:00:00",summary:"Water - Be the Change - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Readers’ Hub (EN)",timest:"5:30 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 18:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 19:00:00",summary:"Meetup - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Stand WCM (MT/EN)",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2022-11-27 19:00:00",endDate:"2022-11-27 20:00:00",summary:"Edit-a-thon - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Stand WCM (MT/EN)",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 09:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 22:00:00",summary:"Il-Kamra Sensorja",timest:"9:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 09:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 22:00:00",summary:"Kwizz u Tqabbil ta’ kliem - German Maltese Circle / Dept. of German, UM - L-Istand tal-GMC / Dept. of German Stand 🇬🇧",timest:"9:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 09:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 22:00:00",summary:"Mural Interattiv tal-Malta Community of Illustrators",timest:"9:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 09:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 22:00:00",summary:"Wirja: Il-Malti: Il-Mixja sal-Għarfien Uffiċjali - Heritage Malta & l-Akkademja tal-Malti",timest:"9:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 09:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 22:00:00",summary:"Wirja: From Illustration To Book - KNK & Il-Kunsill Malti għall-Arti",timest:"9:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 10:30:00",summary:"Produzzjoni teatrali għal studenti tal-primarja - KNK - It-Teatru 🇲🇹",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 10:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: Il-Kavallier Għatxan - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇲🇹",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 11:00:00",summary:"Ejjew nintilfu fit-Tagħrif (5-8 snin) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 11:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 12:30:00",summary:"Ġakki u s-Siġra tal-Fażola (8-12-il sena) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"11:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 12:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 12:30:00",summary:"Produzzjoni teatrali għal studenti tal-primarja - KNK - It-Teatru 🇲🇹",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 12:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 12:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: Osbert and Friends - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇬🇧",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 17:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 18:00:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari mal-awtriċi Sandra Hili Vassallo - Ġemma - L-Istand ta’ Ġemma 🇲🇹",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 17:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 18:00:00",summary:"Animal Bounty! Sessjoni tal-annimali lajv (6-10 snin) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 18:30:00",summary:"Taħdita minn Veronica Veen - Inanna Publishers - L-Istand ta’ Inanna Publishers 🇬🇧",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 19:00:00",summary:"L-Isfida Msella - San Anton u KNK - It-Teatru 🇲🇹",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 19:00:00",summary:"Kif taħdem il-Wikipedija? - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - L-Istand ta’ WCM Stand 🇲🇹/🇬🇧",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 18:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 20:30:00",summary:"Ċerimonja tal-Għoti tal-Premjijiet - The Plaza Prizes - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-18 19:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-18 20:30:00",summary:"L-adattament għall-iskrin – Skemi ta’ sapport tal-Kummissjoni Maltija tal-Films - Kummissjoni Maltija tal-Films - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇬🇧",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 10:30:00",summary:"Produzzjoni teatrali għall-istudenti tal-iskejjel medji u sekondarji - KNK - It-Teatru 🇲🇹",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 11:00:00",summary:"Who is Hiding under the Sea? (9-12 snin) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 10:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: A Journey with the Energetic Four: The Renewables - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇬🇧",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 10:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 12:00:00",summary:"Qari ta’ stejjer dwar il-kelb Shadow - Kite Group - L-Istand ta’ Kite Group 🇬🇧",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 11:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 12:30:00",summary:"Animal Bounty! Sessjoni tal-annimali lajv (9-12-il sena) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"11:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 11:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 12:30:00",summary:"Masterclass minn Sam Blake dwar il-kitba kreattiva għal studenti post-sekondarji - KNK - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"11:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 12:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 12:30:00",summary:"Produzzjoni teatrali għall-istudenti tal-iskejjel medji u sekondarji - KNK - It-Teatru 🇲🇹",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 12:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 12:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: Luna u l-Energetika: Il-Vapur Sostenibbli - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇲🇹",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 17:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 18:00:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari mal-awtriċi Sandra Hili Vassallo - Ġemma - L-Istand ta’ Ġemma 🇲🇹",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 17:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 18:00:00",summary:"Xħin jilagħbu l-Ippopotami? (5-8 snin) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 19:00:00",summary:"Attività ta’ Networking għal-librara flimkien mal-Fondazione per Leggere di Milano u Malta Libraries - Istituto Italiano di Cultura - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇬🇧",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 19:00:00",summary:"Wikipedian-in-Residence at TimesofMalta.com - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Is-Sala fil-Pjazza 🇲🇹/🇬🇧",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 20:00:00",summary:"Il-Promoturi tal-Qari - Aġenzija Nazzjonali tal-Litteriżmu - It-Teatru 🇲🇹",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 18:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 19:30:00",summary:"Masterclass: X’inhi l-istorja tiegħek: 5 passi biex tikteb bestseller - KNK - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 19:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 20:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ Ktieb: 'The First Maltese: How it all Began in Gozo' ta’ Veronica Veen - Inanna Publishers - Is-Sala fil-Pjazza 🇬🇧",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-19 19:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-19 20:30:00",summary:"FRAKASS: poeti kontemporanji - Kotba Calleja - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇲🇹",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 11:00:00",summary:"Inklużi - sessjoni interattiva (9-12-il sena) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 10:30:00",summary:"Produzzjoni teatrali għal studenti tal-primarja - KNK - It-Teatru 🇲🇹",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 10:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: Osbert and Friends - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇬🇧",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 10:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 12:00:00",summary:"Qari ta’ stejjer dwar il-kelb Shadow - Kite Group - L-Istand ta’ Kite Group 🇬🇧",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 11:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 12:30:00",summary:"Triqti lejn il-Ħniena (7-10 snin) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"11:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 12:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 12:30:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari: L-Eroj tal-Ilma - Energy and Water Agency (EWA) - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇲🇹",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 12:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 12:30:00",summary:"Produzzjoni teatrali għal studenti tal-primarja - KNK - It-Teatru 🇲🇹",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 17:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 18:00:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari mal-awtriċi Sandra Hili Vassallo - Ġemma - L-Istand ta’ Ġemma 🇲🇹",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 17:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 18:00:00",summary:"L-Istrixxi Kollha Tiegħi (8-12-il sena) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 19:00:00",summary:"Deċiżjonijiet il-kittieb - skambju bejn Sam Blake u Leanne Ellul dwar l-ideat u l-kliem fil-kitba - KNK - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 19:00:00",summary:"140 ilsien għal Pinokkjo - Istituto Italiano di Cultura - Is-Sala fil-Pjazza 🇮🇹",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 19:00:00",summary:"Kemm Int Drammatiku! - Workshop fuq it-Teatru Malti - Għaqda tal-Malti – Università - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇲🇹",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 19:00:00",summary:"X'inhu Wikidata? - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - L-Istand ta’ WCM 🇲🇹/🇬🇧",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 19:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 20:00:00",summary:"Preżentazzjoni ta’ ktieb: 'Requiem per un fascista maltese' ta’ Francis Ebejer – Bonfirraro Editore – Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇮🇹",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 19:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 20:00:00",summary:"Iltaqa' mal-awtur: Barbi Marković taqra mill-aħħar rumanz tagħha 'Minihorror' (2023) - GMC / UM Department of German - Is-Sala fil-Pjazza 🇩🇪",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 19:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 20:00:00",summary:"Il-Maskulinità fi 'Small Worlds': Serata ta’ qari ma’ LukeReads - Mallia & D’Amato Booksellers - L-Istand ta’ Mallia & D’Amato Booksellers 🇬🇧",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 19:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 20:30:00",summary:"Qari minn 'Jiena u Beppe, Beppe u Jiena' (Merlin Publishers) - MIVC - Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇲🇹",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 19:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 20:30:00",summary:"L-Għoti tal-Premjijiet: Il-Konkors Nazzjonali tal-Poeżija Doreen Micallef 2023 - KNK - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇲🇹",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 20:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 21:30:00",summary:"bħal imrewħa, dal-poeżiji… - vrusha/vrusna - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇲🇹",timest:"8:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-20 20:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-20 21:30:00",summary:"VII / Fidwa - Teatru Malta - It-Teatru",timest:"8:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 11:00:00",summary:"Zinn Zinn Zinn: Mużika u Letteratura għaż-Żgħar u l-Kbar Tagħhom - Għaqda tal-Malti – Università - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇲🇹",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 10:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 11:00:00",summary:"Id-dinja tal-pubblikazzjoni - it-triq lejn is-suq: Masterclass minn Simon Trewin - KNK - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"10:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 10:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 11:00:00",summary:"M&T mat-tim ta’ Ġemma - Ġemma - L-Istand ta’ Ġemma 🇲🇹",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 10:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 11:30:00",summary:"Ħabibħuta fl-Oċean (5-7 snin) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 11:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 11:45:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari ma’ Lucienne Cassar - Pandora Bargain Books - Is-Sala fil-Pjazza 🇲🇹",timest:"11:00 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 11:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 12:30:00",summary:"Il-kitba għat-tfal u ż-żgħażagħ - masterclass minn Charlie Castelletti, editur tal-kotba tat-tfal - KNK - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"11:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 12:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 13:00:00",summary:"Meta jilagħbu l-Ippopotami? (5-8 snin) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 12:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 13:00:00",summary:"Iffirmar ta’ kotba minn Lucienne Cassar - Pandora Bargain Books - L-Istand ta’ Pandora Bargain Books 🇲🇹/🇬🇧",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 13:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 14:00:00",summary:"Workshop minn Jen Calleja u Kat Storace - Praspar Press u l-KNK - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"1:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 13:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 14:00:00",summary:"Mini-art workshops minn Veronica Veen - Inanna Publishers - L-Istand ta’ Inanna Publishers 🇬🇧",timest:"1:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 14:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 15:00:00",summary:"Animal Bounty! Sessjoni tal-annimali lajv (5-12-il sena) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"2:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 15:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 16:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ ktieb: 'The Manor House Governess' (Black and White, Bonnier Books) - rumanz ta’ C.A. Castle - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"3:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 16:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 17:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ 'Scintillas: New Maltese Writing 3' - Praspar Press - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 17:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 18:00:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari mal-awtriċi Sandra Hili Vassallo - Ġemma - L-Istand ta’ Ġemma 🇲🇹",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 17:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 18:30:00",summary:"Iċ-Ċerimonja tal-Għoti tal-Premjijiet Wiki Loves 2023 - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇲🇹/🇬🇧",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 17:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 18:00:00",summary:"Tnedija tal-Commonwealth Short Story Prize f’Malta, mal-kittieba Constantia Soteriou - KNK & Commonwealth Foundation - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 19:00:00",summary:"Tagħrif dwar il-konkorsi tal-fotografija ta' Wikimedia - Wikimedia Community Malta (WCM) - L-Istand ta’ WCM 🇲🇹/🇬🇧",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 19:00:00",summary:"Kif tgħidha f'qalbek: Bejn kitba u traduzzjoni fuq Aphroconfuso - Mallia & D’Amato Booksellers - Is-Sala fil-Pjazza 🇲🇹",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 19:30:00",summary:"[gæp] X’INHU GAP? Taħdita lagħbija fuq il-Liberazzjoni - Ateliersi & Istituto Italiano di Cultura - it-Teatru 🇮🇹",timest:"6:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 18:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 19:15:00",summary:"Kif jinħadem ktieb - Gutenberg Press - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"6:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 19:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 20:00:00",summary:"Ix-xogħlijiet bit-Taljan ta’ Frans Sammut - Bonfirraro editore - Is-Sala tal-Qarrejja 🇮🇹",timest:"7:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 19:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 20:30:00",summary:"Ġibiltà tiġi Malta: tieqa fuq il-letteratura, l-istorja, u l-kultura ta’ Ġibiltà - Il-Kunsill Nazzjonali tal-Ktieb ta' Ġibiltà - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"7:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-21 20:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-21 22:00:00",summary:"Madwar il-mejda mal-kittieba u Jon Mallia - KNK - It-Teatru 🇲🇹",timest:"8:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 10:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 12:00:00",summary:"Qari ta’ stejjer dwar il-kelb Shadow - Kite Group - L-Istand ta’ Kite Group 🇬🇧",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 10:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 11:00:00",summary:"M&T mat-tim ta’ Ġemma - Ġemma - L-Istand ta’ Ġemma 🇲🇹",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 10:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 11:30:00",summary:"Ejjew nintilfu fit-Tagħrif (5-8 snin) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"10:30 AM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 12:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 13:00:00",summary:"Ħabibħuta fl-Oċean (5-7 snin) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"12:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 14:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 15:00:00",summary:"Animal Bounty! Sessjoni tal-annimali lajv (5-12-il sena) – Fondazzjoni Inspire – Il-Kamra Sensorja 🇬🇧",timest:"2:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 14:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 16:00:00",summary:"Tnedija ta’ 'Leħen il-Malti - Għadd 42' - Għaqda tal-Malti – Università - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇲🇹",timest:"2:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 16:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 17:00:00",summary:"Daqq bis-sassofonu u preżentazzjoni ta' 'Gato Barbieri - Una biografia dall'Italia tra jazz, pop e cinema' (ArtDigiland) - Istituto Italiano di Cultura - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇬🇧",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 16:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 17:00:00",summary:"Wiri ta’ film u diskussjoni: Prof. Henry Frendo, Rebbieħ tal-Premju Għall-Kontribut Siewi fil-Qasam tal-Kotba 2022 – KNK – It-Teatru 🇲🇹",timest:"4:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 17:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 18:00:00",summary:"Sessjoni ta’ qari mal-awtriċi Sandra Hili Vassallo - Ġemma - L-Istand ta’ Ġemma 🇲🇹",timest:"5:00 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 17:30:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 18:30:00",summary:"Minn fuq il-karti għal fuq il-palk u l-istejġ: żewġ verżjonijiet ta’ 'Castillo' (Merlin Publishers) - KNK - Is-Sala tal-Kittieba 🇲🇹",timest:"5:30 PM"},{startDate:"2023-10-22 18:00:00",endDate:"2023-10-22 19:00:00",summary:"Preżentazzjoni tal-ktieb 'Raccogliere il mare con un cucchiaino' minn Regina Catrambone (Edizioni Città Nuova) - Istituto Italiano di Cultura - Is-Sala fil-Pjazza 🇮🇹",timest:"6:00 PM"}